History of Lubricants: Reducing Friction, safeguarding our equipment!

Equipment Times traces the ultimate historical timeline of lubricants and lubrication techniques used before the common era to the modern and latest trends in lubricants used in machinery, transport vehicles, appliances, or any other form of industrial technology. Before we

Equipment Times traces the ultimate historical timeline of lubricants and lubrication techniques used before the common era to the modern and latest trends in lubricants used in machinery, transport vehicles, appliances, or any other form of industrial technology.

Before we dive deeper into the history of machine lubrication, let’s consider a quick real-world example. Imagine if we didn’t lubricate train wheels and the other mechanical moving components of a train.

The wheels would get rusted and worn, and would not run smoothly across the train tracks. Our train systems would function at a fraction of their maximum capabilities, and sooner or later, they’d break down.

Can you imagine how costly it would be if trains broke down and had to be replaced every few months? And it’s not just for the government and rail companies. It’s for everyday people who rely on trains for transport to and from work.

It’s important to note that when applying a lubricant to a train, it doesn’t get applied to the tracks, but to the wheels, bearings, engines and other moving components. This would result in the train being unable to move because there would be no friction between the tracks and rails. This same concept can be applied to lubricated components across all industries and sectors.

Proper lubrication helps to extend life, improve operational efficiency, and increase safety for trains and their tracks, along with other environmental benefits. And there are countless other examples throughout history too.

Before the Common Era, animal fats and naturally occurring elements were used for lubrication for chariots and in transporting construction materials. Until about the 18th century, these natural methods were still being used, but oil was then designed and developed for specific purposes.

Today, there is much more research and testing, and different materials are being incorporated, such as grease and other synthetic materials. These materials are now thinner than ever and can be applied to tighter spaces, which is important for modern firearms and defense products.

There are specific oils constructed for even more specific purposes, and our machines—from shipping, to transportation, to industrial factories—work faster and more efficiently than ever. Our world could not function as it does today without modern lubrication advancements.

Our Humble Beginnings

The Stone Age

Humans became familiar with friction back in the Stone Age, when they discovered they could create fire by rubbing wooden sticks together. As the years progressed, men used stone axes and other stone tools to produce similar effects.

It’s believed that primitive men and women hauled logs with their bark removed. Sap would have seeped from the wood and served as lubrication. They’re also believed to have used logs as rolling devices to reduce friction while transporting large loads such as stones, which was also common during the age of the pharaohs.

Other ancient lubricants were mud and crushed long leaves placed under sleds. These sleds were dragged to haul killed animals or building materials such as wood and rocks.

Our lubrication researchers have been able to trace the origin of lubricants back to 3500 B.C.E. and the ancient Egyptians and Sumerians. Using wheeled carts and chariots become common in the Middle East, and these wooden wheels would have become charred because of frictional heat.

Sumerians and Egyptians are believed to have used a variety of ancient lubricants, which included bitumen (a viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum), animal and vegetable oils, and water, to reduce friction on wheels and axles. These ancient people had figured out functional solutions to their problems but still did not understand the science behind friction and lubrication.

To support rigid axles, the Sumerians used inverted forks, along with leather loops, in their carriages. These helped reduce friction along with wear and tear. The Chinese are also believed to have experimented with the lubrication properties of water around this time.

2600 B.C.E

In 2600 B.C.E., lubrication was found in a sled wheel that belonged to an Egyptian pharaoh, which an analysis proved was from beef or ram tallow (a rendered form of beef or mutton fat made up of triglycerides). This discovery led to the determination that ancient Egyptians used tallow as a lubricant for their sleds to transport materials such as wood and rocks.

2000-1700 B.C.E

Egyptian murals from 2000-1700 B.C.E. depict statues being dragged across the ground, with a liquid being poured over a transporting device as a lubricant. It is unknown what these actual liquids were, although they are believed to have been water or olive oil.

Tribology, or the study of friction, wear, lubrication, and the design of bearings enabled ancient Egyptians to increase operating speed and reduce friction. They are also believed to have lubricated their pharaohs’ thrones with olive oil to reduce the manpower needed to push and pull them around.

1400 B.C.E

In the tombs of Yuaa and Thuiu in ancient Egypt, dated around 1400 B.C.E., examples of early chariots were discovered. They were believed to have used tallow along with lime powder and calcium soaps to lubricate chariot axles.

780 B.C.E

The Chinese developed a friction-reducing mixture of vegetable oils and lead by 780 B.C.E.

The first Olympic Games in Greece began in 776 B.C.E., occurring every four years. A common event in the Olympics was horse and chariot racing, where animal fat was used to lubricate the wheel axles.

330 B.C.E

In 330 B.C.E., Diades, a Greek engineer, developed what is believed to be one of the first roller bearing mechanisms to support warship battering rams.

The bearings of a Mesopotamian potter’s wheel from 400 B.C.E. was found to contain traces of bituminous substances (black or dark colored solids derived from petroleum or natural asphalt distillation), suggesting that lubrication from local petroleum deposits was used.

The discovery of a rotating platform in 1930 from a large ship of the Roman Emperor Caligula, dating from around 40 A.D., was found at the bottom of Lake Nemi in Italy. This was the first evidence of ancient rudimentary bearings and a thrust bearing, which is a bearing designed to support direct loads while rotating around its axle.

Into the Common Era

Animal fats and their basic variants continued to be utilized for mechanical lubrication at the start of the Common Era.

200 A.D.

In 200 A.D., the Romans continued to use chariots as a primary form of transportation, which were also lubricated by animal fats.

During the Middle Ages, from the 5th to the 10th centuries, animal fats were known to be used to lubricate the mechanisms for opening the gates of castles & on carriage wheels carrying kings & queens.

The first new changes were reported in 8th century Norway, in the year 780 A.D. At this time, Viking warriors and maritime adventurers were known to be expert boat builders. They created ships known as drakkars, a term derived from the word dragon. Raiders decorated and used these large ships.

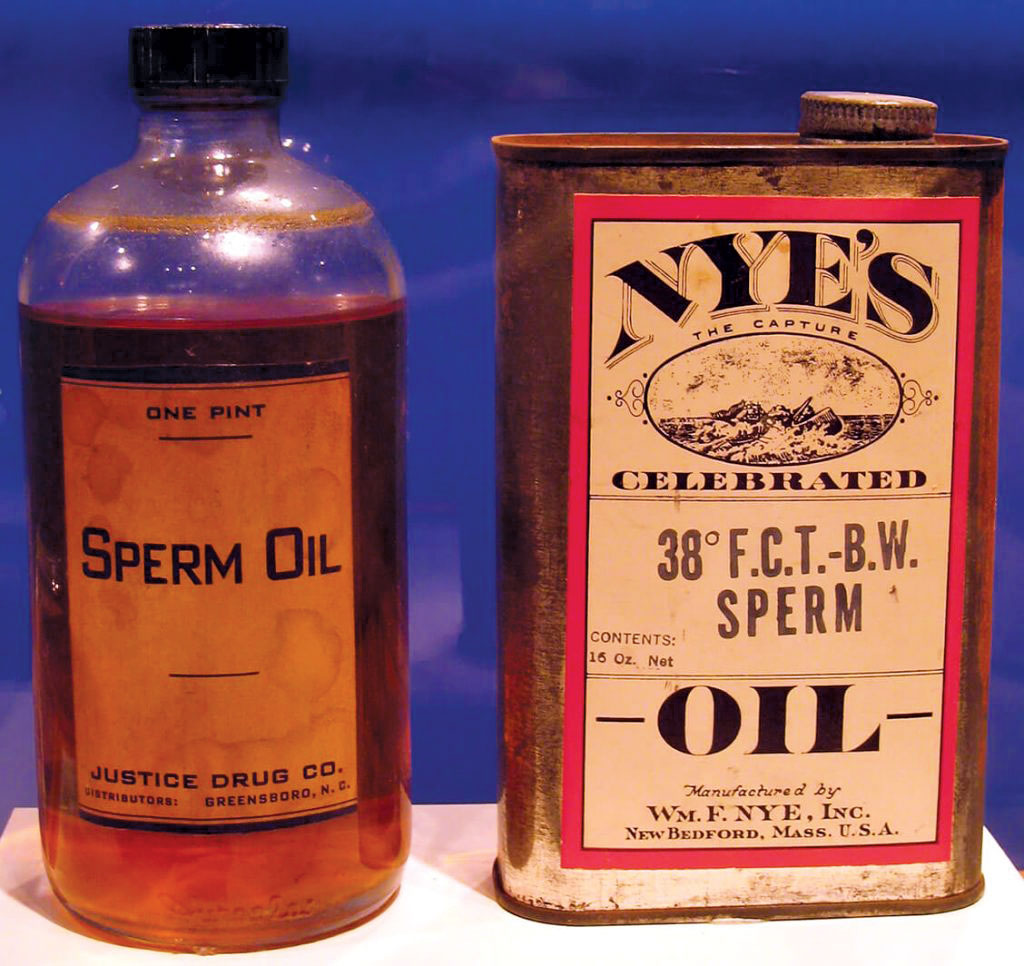

The Norwegians are believed to have used whale oil to lubricate the sails’ hinge supports and the rudder axes. This new type of oil was obtained from the blubber of whale stomachs.

15th Century

The 15th century marked the beginning of improved commercial ship navigation. As a result, whale oil saw continued use in lubricating the pulleys and rudders of ships. It also knew shipbuilders to have used ancient oil methods that had been around for millennia known as rock oil, mineral oil and naphtha oil (flammable oils containing various distilled hydrocarbons).

As civilization continued to develop in Italy through the 15th and 16th centuries, some of the greatest revolutionary minds developed inventions and mechanical tools. One person of note from this time was the great Leonardo da Vinci, who was responsible for developing giant projects that contributed to the advance of mechanical lubrication, such as the catapult and the excavator, among many others.

Throughout his life, Leonardo studied the problem of friction. He examined the coefficient of friction (static friction) on an inclined plane, and determined the value of the friction coefficient as f = ¼. This led to the formulation of the laws of dry friction.

He continued to study friction across horizontal and inclined planes, along with wear on slide bearings. These investigations resulted in his first and second friction laws.

1490

In 1490, he changed the rolling bearing, replacing the moving connection between the two parts with a mechanism that used balls to reduce rolling friction.

His conclusion was that friction was reduced when the balls did not touch, which led to his development of separator elements to let the balls move freely.

As iron and brass replaced wood for many heavy-use machine parts, animal fat oils proved to no longer be adequate. People began to experiment with a mixture of animal and vegetable oils, and some that were developed and are still in use today, such as tallow, olive oil, castor oil (vegetable oil pressed from castor beans), peanut oil, and rapeseed oil (canola).

16th Century

Following the 16th century, whale oil (from whale blubber) use continued, and porpoise oil, retrieved from the body, head, or jaw of a porpoise, came into the picture.

French physicist and governor of Lille, Guillaume Amontons, conducted extensive research on mixed friction. Amontons found that friction force is dependent on normal force along with surface roughness, and developed his theory of “interlocking.”

This led to his derivation of the coefficient of friction to be f = 1/3. Amontons presented his findings in 1699 to the Académie Royale in Paris, but they believed he had just unearthed discoveries attributed to Leonardo da Vinci.

17th & 18th Century

In the 17th and 18th centuries, French natural philosopher John Theophilus Desaguliers developed a tribology model that detailed the effect of cohesion and adhesion on friction. He defined the concept of higher frictional force on well-polished surfaces, as two well-polished surfaces placed together might prove difficult to separate.

In 1687, Sir Isaac Newton, an English physicist and mathematician, defined the term “viscosity,” which centered on the belief that friction had both molecular and mechanical causes. Viscosity today can be defined as “the state of being thick, sticky, and semifluid in consistency, due to internal friction.”

In the 18th century, Swiss mathematician and physicist Leonhard Euler studied the impact of inclined planes on friction, which he determined to be double. He termed this the “friction coefficient.” Charles Augustin Coulomb, a French military engineer and physicist, continued to expand on Amontons’ ideas about surface roughness and mixed friction, along with the connection between horizontal force and weight percent.

In 1794, Philip Vaughan, a Welsh inventor and ironmaster, was granted the first patent for a deep-groove ball, which was an advancement of Leonardo da Vinci’s discovery. This was followed by English horse carriage axles becoming fitted with ball bearings, which required lubrication.

With the Industrial Revolution beginning in the 18th and 19th centuries, mechanization of industry and transportation became a reality. As the textile machinery industry expanded, so did the use of lubricants to ensure the smooth functioning of the machines. Mineral oils from shale and coal were extracted through distillation and refined into petroleum.

We can trace crude oil, or unrefined petroleum, being used as a lubricant back to 1845 and a cotton spinning mill in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The mill owner experimented with this oil by mixing it with the sperm oil he had used to lubricate his spindles.

On August 27, 1859, former American train driver and businessman Colonel William Drake struck oil, marking the birth of the American petroleum industry in Titusville, Pennsylvania. The first oil well was drilled twenty-one meters deep, and soon, 3,200 liters of oil were being extracted daily.

Petroleum-based oils were not accepted on their own as they did not perform like many of the animal-based products. That was until vacuum distillation—or reduction under pressure—showed that useful fractions could be separated without the heavier product oxidizing and deteriorating. Five years after Drake’s big discovery, hundreds of companies became dedicated to oil extraction.

19th Century

As the 19th century progressed, it became common practice to lubricate the bearings of trains every 160 kilometers.

Elijah McCoy, who you may be familiar with from the expression “the real McCoy,” was a Canadian-born African-American inventor and engineer. In 1872, McCoy invented an automatic lubricator that was used to apply oil through a drip cup to locomotive and ship steam engines. He patented this device as an “Improvement in Lubricators for Steam-Engines.”

The term “the real McCoy” is believed to have come about because railroad engineers did not want low-quality copycat versions of this device, so before purchasing it they would ask if it was “the real McCoy.” McCoy went on to own fifty-seven U.S. patents, many of which were related to steam engine lubrication.

As machinery and technology continued to develop further, so did the use of industrial lubrication.

The period between 1850 and 1925 was considered a time of “technical progress,” as the railways became the focus of society’s transportation. Bearings and slideways used liquid lubricants, advancing from solid lubrication (grease precursors). Because of supply and demand, inexpensive lubricants comprising mineral oils were mass produced.

In 1877, French chemist Charles Friedel and American James Mason Crafts developed the first synthetic hydrocarbons. This was the first attempt at a synthetic lubricant alternative.

Between 1883 and 1905, new theories on hydrodynamic lubrication came to light. This was because extensive research showed that adding a lubricated film separated the surfaces of machinery, reducing friction and preventing wear. The added pressure split the two forces apart, coining the phrase hydrodynamic lift.

One person of note from the early 20th century was Oskar Zerkowitz, who emigrated to the United States from Austria and changed his name to “Oscar Ulysses Zerk.” He soon became a famous inventor and was known for a grease fitting he called “the zerk.”

This device became the basis for those used on almost every car, truck, plane, and other mechanized vehicle today. When he passed away in 1986, it was estimated that twenty billion “zerks” had been manufactured, and are still in use today.

Industrial

Anti-friction metal treatment (AFMT) lubricants and greases improve and extend the life of your equipment and protect your investments.

Heat caused by friction reduces the reliability of your equipment and is one of the top causes of machine failure. Metal treatment lubricants and greases penetrate metal surfaces, leaving behind a semi-dry coating reducing friction that lasts six to ten times longer than traditional oil or hydrocarbon based lubricants.

The proper lubrication of industrial equipment can also help reduce maintenance downtime and help you save on electricity, fuel and energy costs. Some common industrial machine parts that can be lubricated include gears, hinges, pulleys, bearings, shafts, axles, chains, cables, joints and pistons.

Conclusion

With a great deal of trial and error, mechanical lubrication has developed over thousands, if not millions of years, from ancient humans dragging logs, to cotton mills in early America, to what it is today across numerous industries and sectors.

Modern lubricants have unlimited applications and uses, whether on machinery, weapons, transport vehicles, appliances, or any other form of industrial technology.

They’re no longer just naturally occurring animal fats, but scientifically formulated synthetic greases and oils that keep our society and advanced moving parts functioning at the highest capacity possible.

Lubrication techniques allow machines to be more efficient, last longer, be more reliable and allow you to spend less money on continued maintenance costs.

Don’t forget: If it moves, it needs to be lubricated.

www.mil-comm.com

Hits: 45